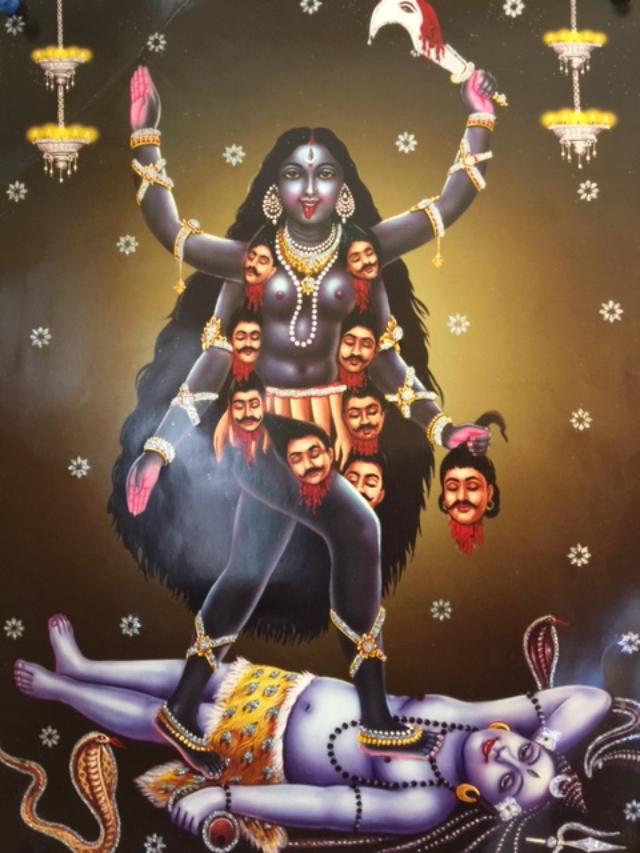

We are all familiar with the goddess Kali’s image: the dark complexion, disheveled hair, tongue sticking out and a garland of human skulls on her is ominous indeed, hardly befitting a goddess. And then there is her husband lying under her feet (is it a precursor to present-day female ‘over emancipation’?). We are so used to the image that we rarely question its origin or significance. From our experience, we would expect the origin to lie in the hoary past (5000 or 10000 years old, depending on how ‘Hindu’ you are). There is surely a Vedic Sukta somewhere hidden in the huge corpus, which may be construed to describe our present goddess. And there would be no dearth profound explanations of deep philosophical significance regarding the various aspects of the image (e.g. the extremely dark skin).

We are all familiar with the goddess Kali’s image: the dark complexion, disheveled hair, tongue sticking out and a garland of human skulls on her is ominous indeed, hardly befitting a goddess. And then there is her husband lying under her feet (is it a precursor to present-day female ‘over emancipation’?). We are so used to the image that we rarely question its origin or significance. From our experience, we would expect the origin to lie in the hoary past (5000 or 10000 years old, depending on how ‘Hindu’ you are). There is surely a Vedic Sukta somewhere hidden in the huge corpus, which may be construed to describe our present goddess. And there would be no dearth profound explanations of deep philosophical significance regarding the various aspects of the image (e.g. the extremely dark skin).

However, to our disappointment, the origin of the image is probably more prosaic and only dates back to around the sixteenth century. It appears that a well-known Tantric went to the river bank before daybreak as part of his daily ritual. There he encountered a dark-skinned woman also taking her bath. The woman was scantily dressed, thus quite taken aback. She stuck her tongue out in shame. The Tantric got visions of Kali in the woman giving rise to the present-day image. I have collected a few samples through Google (where else?) which I present below. They all essentially tell the same story.

Initially, the Goddess Kali was worshiped without any image. People used to pray goddess Kali in a small pot (Ghot)-under a tree. At around 1450 Krishnananda Moitra who was honored with the Title AGAMBAGIS first felt to worship the goddess Kali with a proper IMAGE. One day in deep meditation, Krishnananda invoked goddess kali and sought an image of the goddess. When his sadhana reached ‘Turiya’ state (the highest stage of Kulakundolini) he was instructed that the first lady, whom he would see on the very next day morning, would be the hint of the image. Being too excited he could not sleep and in the wee hour, he started his search. On his way, he saw a low caste black lady who was at that time busy in her domestic works. Her sari was displaced, the vermillion mark was distorted, and both of her hands were full of cow dung. Her right leg was uplifted while she was working. Being too excited Krishnananda shouted – ‘Joy Maa’. As soon as the lady heard this and saw krishnananda, she became ashamed and her tongue came out. Krishnananda captured this in her mind and had drawn the image of Kali. This image is popularly known as Agomeswari Kali or Dakshina Kali. Later many worshipers had drawn various images of Kali as per their own imagination and interpretation – but the basic image remains the same. Agomeswari Kali with all the basic form is still worshipped in Nabadweep, Nadia (Agomeswari Para).

More information on this can be found in the book ‘Mythology of the Hindoos’, written by Reverend William Ward and in various books published by Udbodhan Karyalaya (Ramakrishna Mission Publication).

The detailed description of the image of Goddess Kali can be found in Krishnananda’s book- ‘Brihat Tantrasar‘ (The best book of Tantra Sadhana till date).

It is believed that the present form of Kali is due to a dream by a distinguished scholar of Indian charms and black magic or ‘Tantra’ and the author of Tantric Saar, Krishnananda Agambagish, a contemporary of Lord Chaitanya. In his dream, he was ordered to make her image after the first figure he saw in the morning. At dawn, Krishnanand saw a dark-complexioned maid with a left hand protruding and making cow dung cakes with her right hand. Her body was glowing with white dots. The vermillion spread over her forehead while she was wiping the sweat from her forehead. The hair was untidy. When she came face to face with an elderly Krishnananda, she bit her tongue in shame. This posture of the housemaid was later utilized to envisage the idol of Goddess Kali. Thus was formed the image of Kali.

Sometime in the mid to late 16th century, Krishnananda Agamavagisa, a Bengali mystic (born after 1500) had an apocryphal powerful experience which resulted in a “new” form of Kali. It is said that Krishnananda went to bathe in a river near a cremation-ground (either at Tarapith or Bakreshwar, both in West Bengal), where he happened to stumble upon a dark-skinned tribal – probably Santhal — girl who, believing she was alone, had stripped naked and was washing herself using a discarded skull-cap from a nearby funeral pyre. Her long black hair untied, and she was engrossed in her bathing when some movement made her aware of the watching Krishnananda. Embarrassed the sudden gentleman intruder, she stuck out her tongue in shyness (a reflex action still done by village girls in India). Krishnananda, who had been trying to understand how best to comprehend the many varied forms of divinity, had a sudden and powerful mystical experience, he felt that the skies had opened and he had obtained a direct vision of the primordial female principle. He viewed this tribal girl as a living Kali, and took the “vision” of her naked dark body, long disheveled hair, extended tongue and skull in hand as a new and especially potent icon. The tribal girl symbolizes the hitherto marginalized animism in this story. For the rest of his life, Krishnananda evangelized this special form of Kali far and wide. Around 1580, he wrote the Tantrasara, an ‘Essence of Tantras’, in which he gave the following description of the Dark Goddess and which forms the basis of the typical Bengali Kali icon:

In this context, I cannot help bringing up an event described in Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novel ‘Prothom Alo’ (First Light), a period piece encompassing the times of Rabindranath, Vivekananda, J.C. Bose, etc. In it, he relates an incident where Sister Nivedita was delivering a lecture on Goddess Kali in Albert Hall. She was speaking eloquently to an audience, which included many eminent persons of the time. Suddenly Dr. Mahendralal Sircar (no relation of mine!) stood up and started vociferously heckling the speaker, accusing her, a newcomer to India and Hinduism, of spreading rabid superstitions and pushing back to further darkness. Sister Nivedita tried to explain her position calmly, at which the doctor shot back thunderously: The whole theory of the pujas is mere hypocrisy, deceit. A few Tantrics to whet their sexual appetites have molded an image of a ‘langta magi’(nude woman) and their worship is accompanied by sexual excesses and excessive drinking and meat-eating. The raucous continued with the whole audience involved, till Dr. Sircar left the audience realizing he had very little support. A lot of readers took offense at this description in the novel, to which Sunil Ganguly duly responded alluding to the historical basis of the Kali image.

Now, Dr. Mahendralal Sircar was a very distinguished man. He was one of the earliest MDs from Calcutta Medical College but shifted over to Homeopathy since he felt that way he could better serve the poorer sections of the community. Dr. Sircar treated Ramakrishna Paramahamsa during his last illness. He was in total awe of the saint but his rational mind prevented him from accepting Ramakrishna as an Avatar. And finally, Dr. Sircar may arguably be hailed as the Father of Indian Science. He, almost singlehandedly, with some help from Father Lafont of St. Xavier’s College (a mentor of J.C. Bose) established The Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), the first institution of scientific research in India. IACS is where the Nobel Laureate C. V. Raman did a major part of his early research is still very active in scientific research.

Comments »

No comments yet.

RSS feed for comments on this post. TrackBack URL

Leave a comment