A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE EMERGENCE OF MUSLIMS IN BENGAL

Background and Introduction

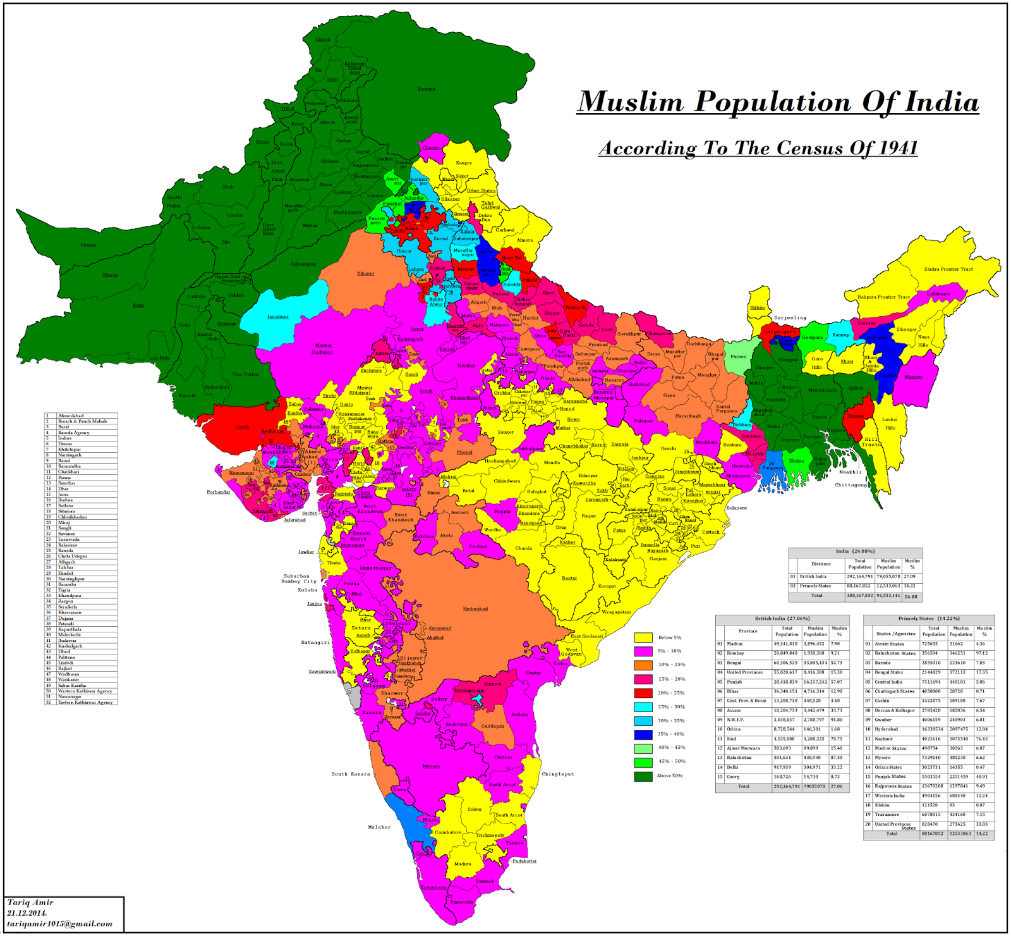

The above map, based on a 1941 census, shows the distribution of the Muslim population in India essentially before independence. The presence of such a high percentage of Muslims in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) in sharp contrast to its contiguous areas with significantly lower percentages is an intriguing one. After all, East Bengal was far away from the sources of major Muslim incursions into India from the northwest, and also from the Muslim power center in Delhi. Even before Partition, East Bengal had 70 percent Muslims, an overwhelming majority among them being peasants and agricultural workers. One wonders how much of this Muslim population represents foreign blood and how much is through conversions.

Bengal was first conquered by Bakhtiyar Khilji in 1204 and Muslims ruled Bengal till Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula was defeated by the British in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The 550-year rule inevitably left its mark in language, art, culture, food habits, and above all, conversions to Islam. One wonders how many conversions took place and, how much of the conversions were by the might of the sword of the Muslim conquerors or garnering favors from them and how much from other sources such as from Arab traders, Sufi preachers or the lower castes trying to escape the cruel Hindu caste prejudices. Or were there other factors?

Significantly, even before Partition, Bengal had a Muslim majority (55 percent); West Bengal had about 30 percent Muslims. This is a far cry from most of the rest of Northern India, even though Bengal’s history was not significantly different from most of North India from the early Muslim period. The society was not significantly different either – similar caste structures and caste prejudices existed in Bengal as in the rest of North India. One big point of difference was the pervasive Buddhism that existed in Bengal when the Muslims first came in. It is a matter of record that the Senas, who ruled Bengal during the first Muslim invasions to Bengal were staunch Hindus (in sharp contrast to the Palas, whom they succeeded, who supported Buddhism) and were highly intolerant towards the Buddhists. Hence erstwhile Buddhists may have converted in large numbers. There are hardly any Buddhists in Bengal today except in the Chakma Hills of Chittagong on the borders of the state. But still, the question remains: why is there such a high incidence of Muslims in East Bengal than the West, since there is no record for a greater presence of Buddhism in East Bengal than West Bengal.

Perhaps the most comprehensive study on the emergence of the Muslim population in Bengal has been presented by Professor Richard M. Eaton of the University of Arizona in his fascinating essay: “Emergence of Muslims in Bengal 1204 to 1760”. In his study, he has made extensive use of textual material from European travelers along with material from Arabic and Persian sources, native (Bengali) sources and recent academic research.

Sultanate Period

Professor Eaton notes that in the Sultanate Period (1204-1554, e.g. prior to Mughal conquest), Bengal’s Muslim society was overwhelmingly urban, concentrated in the sultanate’s successive capital cities—Lakhnauti, Pandua and Gaur and in the provincial towns of Satgaon, Sonargaon, and Chittagong. The population included nobles and merchants which formed part of the Muslim elite, or ashrāf, which also included urban Sufis, religious officials (‘ulamā), and foreign-born soldiers and administrators. In fact, foreign origin, even if only of one’s ancestors, formed an important, if not defining, the element of ashrāf identity. Also, there existed side by side with the ashrāf, but socially distinct from the ashrāf, Muslim urban artisans who formed part of Bengal’s growing industrial proletariat. Their organization into separate, endogamous communities (jāti) with distinctive occupations paralleled the organization of Hindu society in the southwestern delta and suggests their origins in that society. Mukundaram in his Chandi Mangal mentions fifteen Muslim jātis in a list of communities inhabiting an idealized Bengali city of his day, including weavers (jolā), cake sellers (piṭhāri), fishmongers (kābāṛi), loom makers (sānākār), papermakers (kāgajī), wandering holy men (kalandar), tailors (darji), and beef sellers (kasāi). These groups constituted the earliest-known class of Bengali Muslims. Significantly, many of these jatis have Perso-Arabic names. A major observation by Eaton is that the overwhelming presence of Muslim peasants in later years is not evident before the sixteenth century, i.e. the inception of the Mughal period. One wonders if the predominance of Muslim tailors (darjis) in pre-Partition Bengal has its origins in this period.

Mass Conversion to Islam – Theories and Protagonists

Eaton goes on to examine the four most commonly held theories and makes some very interesting observations along with impressive arguments and important conclusions. First off, he cites conclusions from blood group and important anthropometric indicators (Immigration Theory) which clearly establish that the overwhelming majority of Bengali Muslims are of local origin. He then goes on to show that what he calls ‘Conversion by Sword’ theory and the ‘Religion of Patronage’ theory do not fit the religious geography of South Asia. In both cases, he argues with evidence that if Islamization had ever been a function of military or political force, one would expect that those areas exposed most intensively and over the longest period of rule by Muslim dynasties would today contain the greatest number of Muslims. Yet the opposite is the case such as for eastern Bengal or western Punjab, which were on the fringes of the Muslim ruled territories. It does not explain the phenomenon of mass Islamization on the periphery of Muslim power and among millions of peasant cultivators and not just among urban elites. Finally, he examines what he calls the ‘Religion of Social Liberation’ theory, which has for long been the most widely accepted explanation of Islamization in the subcontinent. The theory postulates when Islam “arrived” in the Indian subcontinent, carrying its liberating message of social equality as preached (in most versions of the theory) by Sufi shaikhs, oppressed lower castes, “converted” to Islam en masse in hopes of an escape from the oppression and attainment of social equality. However, present accepted academic research indicates that pre-modern Muslim intellectuals did not stress their religion’s ideal of social equality, but rather Islamic monotheism as opposed to Hindu polytheism (Yohaan Friedmann (1975)). In fact, the idea that Islam fosters social equality (as opposed to religious equality) seems to be a recent notion, dating only from the period of the Enlightenment. Additionally, there is abundant evidence that even upon Islamization, most converts, especially in Bengal, carried the same birth-ascribed rank that they had formerly known in Hindu society. Perhaps this phenomenon is reflected all over India in the presence of the Dalit Muslims. Contemporary estimates indicate that there may be over 100 million Dalit Muslims in India today in a total population of around 200 million Muslims.

From the above, it is evident that neither of the four theories is capable of successfully addressing the primary source of Islamization of Bengal. Further, large numbers of rural Muslims were not observed until as late as the end of the sixteenth century, that is until about the inception of Mughal Rule in Bengal in1574. Our attention must, therefore, turn to the Mughal period in Bengal for the answer.

Mughal Period

If large numbers of rural Muslims were not observed until as late as the end of the sixteenth century or afterward, we face a paradox—namely, that mass Islamization occurred under a regime, the Mughals, who as a matter of policy showed no particular interest in spreading Islam on its subjects. Ruling over a vast empire built upon a bottom-heavy agrarian base, Mughal officials were primarily interested in enhancing agricultural productivity by extracting as much of the surplus wealth of the land as they could, and in using that wealth to the political end of creating loyal clients at every level of administration. Although there were always conservative ‘ulamā who insisted on the emperors’ “duty” to convert the Hindu “infidels” to Islam, such a policy was not in fact implemented in Bengal, even during the reign of the conservative emperor Aurangzeb (1658–1707). However, a fortuitous combination of circumstances occurred with the riverine changes in the delta resulting in added impetus to increased arable land and agricultural activity and consequent demographic changes, and the association of Sufis with the increased populations and agricultural activity. These new situations ushered in a big change as described below.

Riverine Changes and Economic Growth during the Mughal Period

Long term eastern movements of the rivers in Bengal deposited rich silt which made the cultivation of wet rice possible. As the delta’s active portion gravitated eastward, the regions in the west, which received diminishing levels of freshwater and silt, gradually become moribund. Cities and habitations along the banks of abandoned channels declined as diseases associated with stagnant waters took hold of local communities. Thus, the delta as a whole experienced a gradual eastward movement of civilization as pioneers in the more ecologically active regions cut virgin forests, thereby throwing open a widening zone for field agriculture. The process described by dramatically intensified after the late sixteenth century. As contemporary European maps show, this was when the great Ganges river system, abandoning its former channels in western and southern Bengal, linked up with the Padma, the combined Ganges-Padma system linked eastern Bengal with North India at the very moment of Bengal’s political integration with the Mughal Empire. At the same time, the main body of Ganges silt, now carried directly into the east, was deposited over an ever greater area of the eastern delta during annual flooding. This permitted an intensification of cultivation along the larger rivers where rice culture had already been established, and an extension of cultivation into those parts of the interior not yet brought under the plow. As a result, East Bengal attained agricultural and demographic growth at levels no longer possible in the western delta. These changes are reflected above all in the statistics of the Mughal government’s share (khāliṣa) of the land revenue demand (jama‘). Since the revenue demand represents the government’s estimate of the land’s income-generating capacity, and since Bengal’s major income-producing activity was the cultivation of wet rice, a labor-intensive crop, these statistics also suggest changes in the relative population density of different sectors within the delta. Clearance of forests with the advance of wet rice agriculture into formerly forested regions, one of the oldest themes of Bengali history, took a new dimension with the availability of the increased arable land and the population growth. The work was done in large part by local aboriginal people.

Sufis and their Influence

It is widely believed and with good reason that Sufis had a large hand in the conversions to Islam in Bengal. The presence of Sufi saints in the Bengal region was nothing new. Arrival of Sufis to Bengal from the north or even from outside India has been occurring since the beginning of the Muslim rule. Perhaps the most famous of them was Shah Jelal (after whom the Dhaka airport is named). who reportedly arrived in1303 with 360 followers and was a major factor in the spread of Islam in Sylhet and Assam. Ibn Batuta, the famous world traveler indicates in his travelogue of having met Shah Jelal. However, from at least the sixteenth century onwards there started the association of Muslim holy men (pīr), or charismatic persons popularly identified as such, with forest clearing and land reclamation. In popular memory, some of these men swelled into vivid mythic-historical figures, saints whose lives served as metaphors for the expansion of both religion and agriculture. They find mention in oral traditions as Bengali literature of the period. Mention may be made of Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabriz of Pandua, Meher Ali of Jessore, Shah Sayid Nasir of Sylhet, Khondkar Shah Alam of Midnapur, Zinda Gazi, Mubarak Gazi, Khan Jehan in Khulna, Umar Shah in Khulna, Bade Gazi Khan and Zafar Mian.

The conversion process seems to have continued into the nineteenth century. According to Encyclopedia Britannica (1974), as late as 1872, when a census was taken, Hindus still outnumbered Muslims in Bengal (18 million to 16 million). The balance began to tilt towards the Muslims from the 1890s, which is attributed primarily to the significant activity of the Sufis. Other reasons for the change indicated include migration on Muslims from other parts of India and outside India into Bengal and a higher birth rate attributed to Hindu widows not being allowed to marry.

Later Movements

Two later movements that caught the imagination of rural Bengal perhaps deserve a mention. The Faraizi movement started by Haji Sharaitullah in 1818 was probably more significant. The movement concentrated largely in districts of East Bengal like Dhaka, Mymensingh, Faridpur, Barisal and Comilla captured the imagination of the peasant class and acquired the characteristics of a zamindar-peasant divide. The movement seems to have petered out after the death of Dudu Miya, the son of Shariatullah, who succeeded him as the leader. In another significant movement, a rebellion led by Titu Mir led to Titu Mir’s declaration of independence from the British, regions comprising the current districts of 24 Parganas, Nadia and Faridpur. The followers of Titu Mir believed to have grown to 15,000 and armed with nothing more than the bamboo quarterstaff and Lathi and a few swords and spears were finally overwhelmed by a British force in1831. It is not evident that either of these movements had any significant effect on the Islamization of these areas which have an overwhelming presence of Muslim peasants.

References

Eaton, Richard M., “ The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993

Yohanan Friedmann, “Medieval Muslim Views of Indian Religions,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 95 (1975): 214–21

Comments »

No comments yet.

RSS feed for comments on this post. TrackBack URL

Leave a comment